I wrote a book review after ages, but then this was a special kind of book. The review is just out in Biblio, and will be up soon at www.biblio-india.org.

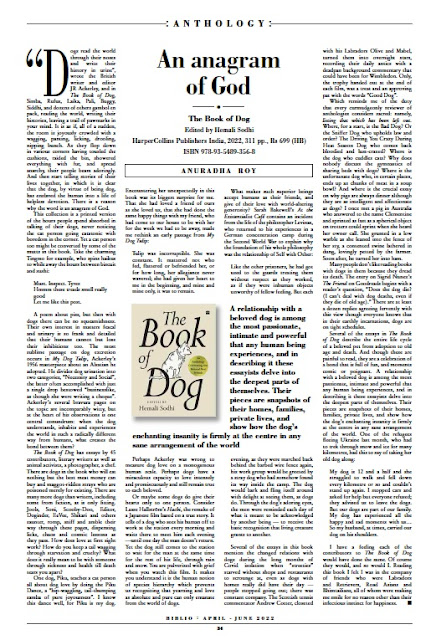

THE BOOK OF DOG is edited

by Hemali Sodhi is a beautiful hardback of 311 pages and is priced Rs 699. It is published by HarperCollins India.

___

“Dogs read the world through their noses and write their history in urine”, wrote J. R. Ackerley, and in The Book of Dog, Simba, Rufus, Laika, Pali, Buggy, Siddhi, and dozens of others gambol en pack, reading the world, writing their histories, leaving a trail of pawmarks in your mind. It is as if, all of a sudden, the room is joyously crowded with a wagging, panting, licking, drooling, nipping bunch. As they flop down in various corners having tousled the cushions, raided the bin, showered everything with fur, and spread anarchy, their people beam adoringly. And then start telling stories of their lives together, in which it is clear that the dog, by virtue of being dog, has enslaved the human into a life of helpless devotion. There is a reason why the word is an anagram of God.

This collection is a printed version of the hours people spend absorbed in talking of their dogs, never noticing the cat person going catatonic with boredom in the corner. Yet a cat person too might be converted by some of the mutts in this book. Take the charming Tingmo for example, who spins haikus to while away the hours between biscuit and sushi:

“Must. Inspect. Tyres

Hmmm these treads smell really good

Let me like this post.”

A poem about piss, but then with dogs there can be no squeamishness. Their own interest in matters faecal and urinary is so frank and detailed that their humans cannot but lose their inhibitions too. The most sublime passage on dog excretion occurs in My Dog Tulip, Ackerley’s 1956 masterpiece about an Alsatian he adopted. He divides dog urination into two categories, “Necessity and Social”, the latter often accomplished with just a single drop bestowed “businesslike, as though she were writing a cheque.” Ackerley’s several bravura pages on the topic are incomparably witty, but at the heart of his observations is one central conundrum: when the dog understands, inhabits and experiences the world in such a radically different way from humans, what creates the bond between them?

The Book of Dogs has essays by forty-five contributors, literary writers as well as animal activists, a photographer, a chef. There are dogs in the book who will eat nothing but the best meat money can buy and maggot-ridden strays who are poisoned merely for existing. There are many more dogs than writers, including some from fiction, as is only fitting. Jools, Soni, Scooby-Doo, Editor, Doginder, EeVee, Shikari and others saunter, romp, sniff and amble their way through these pages, dispensing licks, chaos, and cosmic lessons as they pass. How does love at first sight work? How do you keep a tail wagging through starvation and cruelty? What does it really mean to be with someone through sickness and health till death tears you apart?

One dog, Piku, teaches a cat person all about dog love by doing the Piku Dance, a “hip-waggling, tail-thumping samba of pure joyousness”. I know this dance well, for Piku is my dog. Encountering her unexpectedly in this book was its biggest surprise for me. That she had loved a friend of ours as she loved us, that she had done the same happy things with my friend, who had come to our house to be with her for the week we had to be away, made me rethink an early passage from My Dog Tulip:

“Tulip was incorruptible. She was constant. It mattered not who fed, flattered or befriended her, or for how long, her allegiance never wavered; she had given her heart to me in the beginning, and mine and mine only, it was to remain.”

Perhaps Ackerley was wrong to measure dog love on a monogamous human scale. Perhaps dogs have a miraculous capacity to love intensely and promiscuously and still remain true to each beloved.

Or maybe some dogs do give their hearts only to one person. Consider Lasse Hallström’s Hachi, the remake of a Japanese film based on a true story. It tells of a dog who sees his human off to work at the station every morning and waits there to meet him each evening – until one day the man doesn’t return. Yet the dog still comes to the station to wait for the man at the same time for the rest of his life, through rain and snow. You are pulverized with grief when you watch this film. It makes you understand it is the human notion of species hierarchy which prevents us recognising that yearning and love as absolute and pure can only emanate from the world of dogs.

What makes such superior beings accept humans as their friends, and give of their love with world-altering generosity? Sarah Bakewell’s At the Existentialist Café contains an incident from the life of the philosopher Levinas, who returned to his experiences in a German concentration camp during the second world war to explain why the foundation of his whole philosophy was the relationship of Self with Other:

“Like the other prisoners, he had got used to the guards treating them without respect as they worked, as if they were inhuman objects unworthy of fellow feeling. But each evening, as they were marched back behind the barbed wire fence again, his work group would be greeted by a stray dog who had somehow found its way inside the camp. The dog would bark and fling itself around with delight at seeing them, as dogs do. Through the dog’s adoring eyes, the men were reminded each day of what it meant to be acknowledged by another being – to receive the basic recognition that living creature grants to another.”

Several of the essays in this book mention the changed relations with dogs during the long months of Covid isolation when “streeties” starved without shops and restaurants to scrounge at, even as dogs with homes really did have their day – people stopped going out; there was constant company. The Scottish tennis commentator Andrew Cotter, closeted with his Labradors Olive and Mabel, turned them into overnight stars, recording their daily antics with a deadpan background commentary that could have been for Wimbledon. Only, the trophy handed out at the end of each film, was a treat and an approving pat with the words “Good Dog”.

Which reminds me of the duty that every curmudgeonly reviewer of anthologies considers sacred: namely, listing that which has been left out. Where, for a start, is the Bad Dog? Or the Sniffer Dog who upholds law and order? The Driving You Crazy During Heat Season Dog who comes back bloodied and lust-crazed? Where is the dog who cuddles cats? Why does nobody discuss the gymnastics of sharing beds with dogs? Where is the unfortunate dog who, in certain places, ends up as chunks of meat in a soup bowl? And where is the crucial essay on why pigs are always dinner although they are as intelligent and affectionate as dogs? I once met a pig in Australia who answered to the name Clementine and sprinted as fast as a spherical object on trotters could sprint when she heard her owner call. She grunted in a low warble as she leaned into the fence of her sty, a contented swine lathered in dung, lovingly petted by the farmer. Soon after, he turned her into ham.

Many people don’t like reading books with dogs in them because they dread its death. The entry on Sigrid Nunez’s The Friend on Goodreads begins with a reader’s question, “Does the dog die? (I can't deal with dog deaths, even if they die of old age).” There are at least a dozen replies agreeing fervently with this view though everyone knows that in their earthly incarnations, dogs are on tight schedules.

Several of the essays in The Book of Dog describe the entire life cycle of a beloved pet from adoption to old age and death. And though these are painful to read, they are a celebration of a bond that is full of fun, and moments comic or poignant. A relationship with a beloved dog is among the most passionate, intimate and powerful that any human being experiences, and in describing it these essayists delve into the deepest parts of themselves. Their pieces are snapshots of their homes, families, private lives, and show how the dog’s enchanting insanity is firmly at the centre in any sane arrangement of the world. One of the refugees fleeing Ukraine last month, who had to trek through snow and ice for many kilometres, had this to say of taking her old dogs along:

“My dog is 12 and a half and she struggled to walk and fell down every kilometre or so and couldn’t stand up again. I stopped cars and asked for help but everyone refused; they advised us to leave the dogs. But our dogs are part of our family. My dog has experienced all the happy and sad moments with us… So my husband, at times, carried our dog on his shoulders.”

I have a feeling each of the contributors to The Book of Dog would have done the same. Of course they would, and so would I. Reading this book I felt I was in the company of friends who were Labradors and Retrievers, Road Asians and Bhimtailians, all of whom were making me smile for no reason other than their infectious instinct for happiness.

__